Interesting new report from RAND. Download the PDF here

Category: Terrorism

Al-Shabaab Now

Based on open source material and testimony from recent defectors, the aim of this post is to provide an insight into the current state of al-Shabaab (aS).

As we enter Ramadan, a period that is traditionally accompanied by an upsurge in violence, and then the 2016 Elections period (due to conclude on 20AUG16) and which will, inevitably, also be the focus of aS operations, it is useful to assess the state of aS. However, this is only an assessment: it is based on the limited sources available and it should not, therefore, guaranteed to be completely accurate nor should strategic decisions be based upon it.

At the same time, this does not represent the views of any institution or any individual other than Our Man on the Horn.

Overview

Despite losing a considerable amount of territory, aS still retains control of about 20% of the South/Central Somalia including the Jubba River Valley, as illustrated by the two AMISOM-produced maps below.

Figure 1: aS Loss of Territory JAN-OCT2014

January 2014

October 2014

In particular, aS remains capable of mounting attacks against the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), the Somali security forces, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), the international community and neighbouring countries. aS faces many challenges: but is by no means a spent force since, like many terrorist groups, it is flexible, scalable and survivable.

Organisation

In terms of numbers, aS is estimated to have at most 13-14,000 personnel, although many are merely supporters or involved in non-combat activities. But anything up to half are members of Jabahaat (military wing) or Amniyat (secret police/ intelligence).

In terms of demographics, the majority of foot soldiers are aged 15-25, have at best primary level education and are from rural backgrounds. Reasons for joining vary: financial, for adventure, grievance-based vengeance, nationalist impulses, religious ideology or simply that they were ordered to join by elders as part of clan commitments to provide fighters. Commanders, on the other hand, are generally better educated, more ideologically motivated and have strong links to other, more senior commanders.

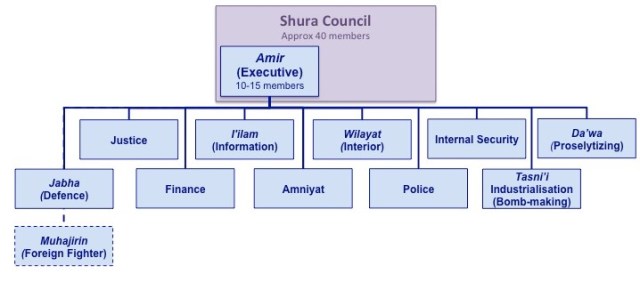

A representation of the overall governance structure of al-Shabaab, which is by no means exhaustive, is given below.

Figure 2: aS Organisation

- Jabahaat (Defence) is in charge of defence and the conduct of military operations. It has both Regular, territory-focussed Divisions as well as Special Brigade units (these should not be confused with the ‘Named Brigades’ referred to in video products, which are drawn from across the organisation for specific operations).

- Muhajirin is responsible for the administration of non-ethnic Somali foreigners who are dispersed across the different departments.

- Justice is of interest in its role as a travelling impartial court: members become experts in clan dynamics as well as Shura law. This reflects key elements of al-Shabaab’s enduring appeal: seeming incorruptibility and cultural affinity.

- L’ilal (Information) is the mouthpiece of aS, responsible for managing all of its media outlets such as well as special propaganda productions (in co-operation with aQ’s media house, al-Kutaib).

- Amniyat is one of the most important as well as notorious offices of the organisation and is focussed on covert operations, both internally and externally.

- The Finance office is the lifeblood of the organisation, in charge of income streams as well as the subsequent distribution of monies.

- Wilayat (Interior) is responsible for all internal policies with regards to community engagement, internal security, and management of regional policies.

- Tasni’i (Industrialisation or Bomb-Making) is the military design element of the organisation, which is responsible for efforts such as making explosive devices.

- Da’wa, on the other hand, is often mistaken for Recruitment, whereas it is in fact a loose grouping of religious authorities who are also well versed in persuasive rhetoric. Da’wa does not have a guaranteed place on the Executive.

This structure is fluid, reflecting the changing needs of the organisation; elements are added and removed as required. In 2009, for instance, the Foreign Fighters office was created to appease a senior leader, Nabha. Its commander was added into the Executive in order to contain the potential threat from that volatile group.

Each element has its own individual structure that fits its task but all are designed to be robust, with at least two deputies under each minister/Emir. This is presumably designed to address the reality of the situation for the leadership of al-Shabaab: they regularly meet an untimely death. However, this also allows for the regular rotation of personnel without a loss of institutional knowledge.

Jabahaat (Defence) is particularly interesting. Using up roughly 70% of the outputs of Finance’s activities, Jabahaat apparently mimics the structure of the Ethiopian military (various entities were studied and the ENDF was agreed to be the most relevant to the formative al-Shabaab). The structure of Jabahaat is shown below.

Figure 3: Jabahaat Structure

As well as five regional Jabhas (Divisons/Brigades) covering the areas that al-Shabaab currently or up until recently controlled (and where it often still operates – such as Mogadishu city), three additional Special Jabhas cover other territories of interest to al-Shabaab: Puntland in north eastern Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya.

However, these ‘Special Jabhas’ should not be confused with the Special Forces Brigade used in the attacks on AMISOM positions in Southern Somalia. Commonly referred to as the ‘Abu Zubayr Brigade’ (in memory of the former leader of aS, Godane, killed in a US drone strike on 01SEP14). This regular unit leads large-scale attacks on isolated AMISOM & SNA positions in the hinterland of South/Central Somalia (such as the recent Leego, Janaale and El Adde attacks). It is viewed as being an ‘elite’ unit and is modelled, ironically, on Israeli Special Forces. (Occasionally the brigade uses the name Nabha Brigade as a provocation to the Kenyans – Nabha was a Kenyan-Somali, so this alias was eminently suitable for the attack on the Kenyan forces at El Adde.)

Being a member of the Abu Zubayr Brigade brings benefits beyond the mere kudos of being in an elite unit: those who participated in the recent attack on the AMISOM (KDF) position at El Adde apparently received a $400 bonus and 2 months leave; commanders were promoted.

Challenges for aS

aS currently faces many challenges. Many revenue streams have been lost or have dwindled. Illicit trade in charcoal, counterfeit goods and smuggling have all been interfered with by aS’s loss of control of the Somali littoral and the counter piracy maritime blockade means aS can no longer levy harbour fees on pirate gangs.

Since aS is no longer in control of ground it is no longer in control of people so it can no longer levy zakat or taxes. Donations from abroad via money transfer (hawalada) have effectively ended with the withdrawal of international banking support. As a result, aS has increased tax on the areas it does control with a commensurate loss of public support.

(However, despite numerous media stories to the contrary, it should be noted that there is no convincing evidence of ivory/endangered species smuggling.)

aS is also suffering the effects of attrition in two ways: members being killed or captured and defections (both leaders and foot-soldiers). The effects of attrition are all too clearly seen in the increasing recruitment (possibly press-ganging) of younger rural males, many of whom are, by western definition, child soldiers (although aS defines adulthood as being aged 15 years or older).

Strikes (the use of air power – drones and so on- and, increasingly, Special Forces raids), while controversial due to misuse/negligence in other theatres, are causing significant losses to the organisation. According to recent defectors, strikes are also having an effect on morale at all levels, a reflection of aS’s lack of air power, and absence of effective anti-aircraft systems and the inability to function at night. Strikes also cause significant disruption to aS communications and general pattern of life (avoiding concentrations, eschewing the use of cellphones and so on).

On the other hand, defections are also undermining aS’s ability to operate. Defections prompt resource intensive internal policing and purges, the promote distrust while at the same time posing little risk to the FGS and its allies. Significantly, in the last 18 months hundreds of footsoldiers have defected as well as 14 leaders (3 senior, 11 mid-level). Even more significant is the fact that those leaders come from a variety of clans, roles and locations. This is a trend, not a glitch.

The final challenge for aS is of an ideological and therefore potentially existential nature. aS continues to go through a period of internal friction over its future direction: is it still part of the global jihad, linked to al-Qa’ida? or is it a nationalist organisation fighting to rid the country of foreign invaders and their apostate lackies?

More recently, another schism has emerged: should aS remain loyal to al-Qa’ida or shift its support to IS/Da’esh, as one clan-focussed faction has done? aS is currently rife with barely suppressed divisions.

aS Strengths

However, aS is by no means finished as a violent insurgent force in Somalia and the region. aS continues to be able to operate with ease across the frontlines into FGS controlled areas and across borders into similarly volatile neighbouring countries such as Kenya and Yemen. It has also proven itself to be flexible, scalable and survivable, and this has allowed aS to continue to conduct not one but three lines of operation. ‘The 3-Pronged Approach’ that aS operates consists of urban terrorism, rural guerrilla warfare and transnational sectarianism.

aS specialises in the ‘propaganda of the deed’. Using urban terrorism as an example, since abandoning the city of Mogadishu in 2011, aS has mounted a campaign attacks against significant individuals (MPs, senior security forces personnel and so on), institutions, key locations (especially hotels) and high profile groups in society (journalists, women, the international community and so on).

For example, attacks in the city of Mogadishu in the first quarter of 2015 are shown below:

Figure 4: HPAs in Q1 2015

- 22JAN: SYL hotel attack

- 09FEB: MP assassinated in Hamar Weyne

- 17FEB: Immigration personnel shot dead in vehicle near K4

- 20FEB: Central Hotel attack

- 21FEB: 3 VBIEDs reported roaming the streets

- 28FEB: VBIED targeting security forces intercepted

- 05MAR: Heightened threat to MIA for 72 hours

- 11MAR: VBIED rear Makka-al-Makarama Road

- 27MAR: VBIED and suicide squad on Makka-al-Makarama Hotel

This meant that every 10-14 days aS mounted a High Profile Attack (HPA). While not all were successful and even some successful attacks yielded little in terms of casualties other than the attackers, the symbolism of being able to operate in the capital with impunity had the desired effect on public confidence. After a lull, it is worth noting that aS’s tempo of attacks is once again nearing early 2015 levels.

aS Communications

aS is also effective at communicating in ways other than attacks. aS retains a clear, consistent & simple ideology (outwardly at least) that remains attractive in isolated components, especially to those with limited perspectives (rural population, some Diaspora). aS has clear, simple lines of messaging that resonate: they are the most Somali, the most religious, the most capable of providing security and the most capable of providing services. aS messages at a high tempo in each of these areas concurrently.

aS also has a very effective mass communications operation which (its own organic production capability, al-Kataib) produces high quality one-off video products for distribution on the internet. Notable recent products include the foiled French SF Raid, the assault on Kodha Island, the attack on Westgate Mall in Nairobi, the cross-border incursion into Lamu County in Kenya and the over-running of the AMISOM bases at Leego, Janaale and El Adde. Products are produced in Somali, Arabic, Swahili and English.

Kodha Island is notable as it proves that aS actually does something that many institutions claim but actually never do: aS places the effect on public perception at the heart of their operational planning. This makes them considerably more adept than those they oppose. There was no reason to invade Kodha Island, except to produce a video product: no tactical gain (they left after 3 days), no resource to be purloined, no key individuals to be killed or captured. Just to make a video.

FOOTNOTE: The IS/Da’esh Faction

The final factor to be considered is the emergence of a dissident faction that has instead sworn allegiance to IS/Da’esh.

This group was initially small in number (28) and focussed entirely on a disaffected group of Darood in the Galgala Mountains of Puntland. Others have since joined them but it is assessed that the group still numbers less than 100. While aS reacted cautiously to the initial declaration, responding only with statements from senior figures, it was soon realised that the IS/Da’esh faction had gained some traction and a purge was launched.

Many of those who have attempted to join the IS/Da’esh faction have been victims of the purge, leaders being executed and foot soldiers being sent for ‘re-education’. Some foreign fighters (a term that aS uses to refer to members of the Somali Diaspora as well as the small number of non-ethnic Somalis in the organisation) have deserted and attempted to join IS/Da’esh in Puntland or elsewhere and have been captured by the government. aS’s recent ill-thought through amphibious assault on Puntland is thought to have been focussed on wiping out the IS/Da’esh faction, although it ended in an ignominious failure.

The IS/Da’esh issue is by no means yet resolved in aS’s favour. However, the media coverage, possibly stoked by the actions of some government institutions and elements of the international community, has been hysterical and has grossly over-inflated the strength and influence of the IS/Da’esh faction. This may, unfortunately, have the effect of allowing the IS/Da’esh faction to establish itself permanently in Somalia.

Thank you…

Cheers, chums – topped the previous Monthly figures on Our Man on the Horn (NOV15), and in just four days.

Resolution: I will update Our Man on the Horn more frequently…

Let me know what you want to see at @ourmanonthehorn

Seeds of Doubt: The El Adde Edit

It’s all about the video… An al-Shabaab cameraman films during the El Adde Attack

As al-Shabaab video products go, it’s not one of the better ones. While not as sprawling as the one-and-a-half hour Mpeketoni product, it is still a ponderous 48 minutes long (try blue-toothing that to your pal). Like the Mpeketoni video, a great deal of the build-up focuses on imagery of Muslims being abused by Kenyan security forces, followed by a reminder of the ‘body count’ of al-Shabaab’s various forays into Kenya (Westgate, Lamu County, Garissa, Mandera) carried out in apparent direct reprisal for and in defence of the oppressed Muslims of East Africa. (The logic of reminding the audience of atrocities, each almost exclusively against civilians, is questionable.)

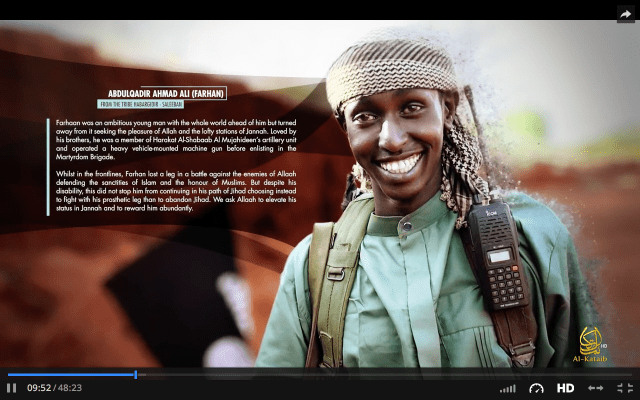

Monoped Farhan: not much use for anything else except suicide bombing

After the obligatory, lengthy suicide bomber ‘leaving speech’ (monoped Farhan of the Habargidir – not much use for anything else after he lost his leg, we must assume), the attack begins in the same old way, with a flash against the dawn skyline.

The attack, too, is very much akin to the previous video products produced on al-Shabaab’s behalf by al-Kutaib, al-Qa’ida’s media house. Technicals mounting Dushka heavy machine guns, twin 23mm anti-aircraft cannon go back and forwards. Plenty of ammunition is expended (sometimes aimed, mostly not), PK machine guns are fired from the hip and above the head, RPGs and heavy recoilless rifles engage targets (although two unfortunates standing behind one of the recoilless rifles appear to take the backblast in the face). Loose lines of troops advance at a gentle pace and begin to overrun the hotch-potch AMISOM position. Apparent leaders, rifles slung over their shoulders, kneel, speak into Tetra-style radios, give some direction. Most of the troops wear the proud badge of the Abu Zubayr Brigade, a bright orange flash, either as a head or arm-band.

A profusion of orange head- and arm-bands: not so much bravado as a simple control measure for troops unused to fighting as a unit

But there are jarring notes throughout, not just for the two clowns who forgot that some of the fiery fury that comes out the front of the recoilless rifle also comes out the back as well. Those bright orange bands must make nice aiming marks and, as much as they might be a piece of bravado, they might also be a unit marker, needed to a coordinate a loose rag-tag that has come together for the operation, probably never having worked as a formed unit before. (There are also some blue bands to be seen later in the video.)

More questioning of what we seem to be seeing. A colleague comments, ‘it’s some men firing at some bushes’: and she is right. For most of the video, we willingly suspend our disbelief and go along with al-Shabaab’s version of events. But most of the video is just that, men firing at some bushes, or a tarpaulin, or something, maybe a running man, in the distance.

Occasionally the fighters do shoot at a target – it takes a section strength group a few minutes, a few hundred rounds to hit a prone, probably already dead AMISOM soldier at a distance of about 30 metres. Despite the apparent profusion of anti-armour weapons (according to the editing at least), an AMISOM-tagged armoured car meanders through melee, does some ‘turning in the road using forward and reverse gears’ and goes away again.

Al-Shabaab uses the Kenyan government’s ill-judged messaging against it – again

The fighting putters out and, again, to a format, we view some burning vehicles, the shooting of some soldiers who are already dead, boxes and boxes of ammunition being carried away, imagery of al-Shabaab fighters wandering around a deserted town, a slideshow of dead bodies. The video product ends with the standard judo flipping of ill-judged Kenyan government and military messages set against apparently contradictory video evidence (the Kenyans really must ditch the ‘aspirational messaging’– al-Shabaab throws this back at them every time).

But numerous seeds of doubt are planted by this product. Yes, the Kenyans obviously lost a lot of troops: it was pointless and it continues to be pointless to claim otherwise. But virtually every one of the corpses is in helmet and body armour, holding a rifle. These men died fighting, and, small compensation to their families as that is, it is how soldiers are meant to die in battle. That deserves recognition.

Which leads to another point: where are the al-Shabaab casualties? Recently defected former fighters claim that al-Shabaab suffered something like 50% dead and wounded in the El Adde attack. Judging by their still-much-too-close spacing, their gentle, strolling pace as they advance and the atrocious marksmanship, that is feasible, especially when the Kenyan light armour started engaging. It is easy to forget that this is an edit, a propaganda product with a deliberate effect in mind, something to be taken with a very large pinch of salt and set against a backdrop of a disastrous, illogical amphibious assault in Puntland (probably 200+ killed out of 400) and a series of drone strikes (Raso Camp: nearly 200 killed) and special forces raids (various senior leaders killed). But, and in spite of over $20 million worth of communications projects focussed on Somalia, a plethora of radio stations, TV channels, websites and a purported ‘getting’ of Strategic Communications (after ten years of trying to ‘get’ Strat Comms in two other long CT/COIN campaigns), there is still no real challenge to al-Shabaab’s inconsistency-ridden messaging. No-one is answering the questions these video products pose.

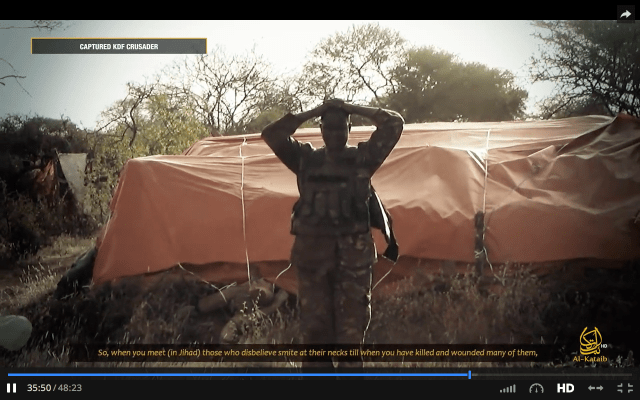

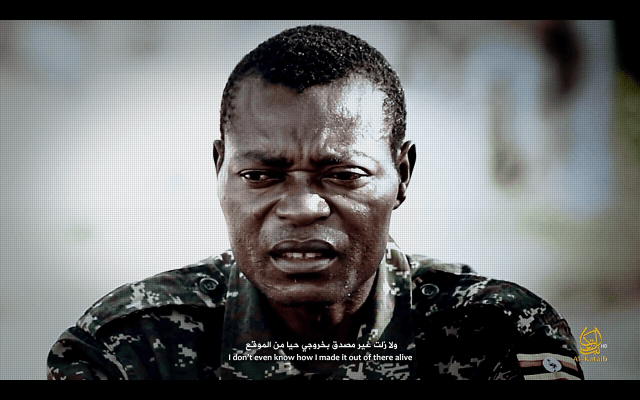

Hardest to forget, though, is the chilling sequence where a dazed Kenyan crewman appears out of the hatch of a stalled armoured vehicle. After a long section that captures his bewilderment all too well he is fired at, finally some of the rounds hit, he slumps, dies. That, along with an ominous message that many of the captured-and-paraded Kenyan troops subsequently ‘succumbed to their injuries while others still remain in captivity and their fate hangs by a thread’, has ramifications that we should not forget whilst caught up in an exciting video re-enactment of a battle. These are war crimes, outrages against humanity, and, one day, some of these murdering bastards should be held to account for that.

War crimes: a captured AMISOM soldier whose life, ominously, ‘hangs by a thread’

NOTE: as a matter of policy and out of respect to the dead we do not publish imagery of the dead: we counter propaganda, not amplify it

Hmmm… – 3

Putting aside the inevitable geek-ish questions about RAND’s methodology, how they defined a terrorist groups, CT campaigns that combined elements and so on, this pie chart is thought provoking.

If so few terrorist groups end as a result of military force (al-Qa’ida in Iraq, Tamil Tigers), why do governments continue to default to that approach? More terrorist groups actually achieve their goals than are defeated by military force, and the vast majority are driven out of business by policing and politicisation. But policing and politicisation are costly and take time, whereas we have all these soldiers standing around doing nothing…

‘Hmmm…’ is a series of short observations, too long for Twitter, too short for a proper posting.

Hmmm… – 2

On the anniversary of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, by far the best and most balanced, insightful response I saw at the time was cartoonist, Joe Sacco’s ‘On Satire’. By all means post ‘Je Suis..’ or colour in your F*c*book profile pic – but they don’t require deep thought about what is really going on.

What’s in a Name?

Why are we calling a group that is neither Islamic nor a state ‘the Islamic State’?

ANOTHER day, another conference on counter terrorism, or whatever we’re calling it this week. I’ve been on the circuit long enough to know the format: academic presentations, some of which are insightful, some statistical, some irrelevant, some just plain bizarre; a chance to learn the latest buzzwords, keep up with the latest fads (COIN – out, CVE – in); the social side, where the real business is done; and a nice break in a nice hotel in a nice city (Rome, Riga, Lisbon, Abu Dhabi and, on this occasion, Ankara). Oh, and the obligatory participant with a tangential point to make, a drum to beat throughout the conference/workshop/course.

Except this time, while the point is made regularly throughout the conference like the chiming of the clock, it is not tangential. If anything, it is fundamental to the discussion of counter terrorism right now and it comes, appropriately, from a Tunisian army officer, and is echoed variously by Turkish, Pakistani and Jordanian participants. We need to stop calling ‘it’ the Islamic State.

I normally prickle at the use of ‘we’ (in my experience ‘we need to do something’ usually means I end up having to do a lot of work) but my Tunisian comrade is correct – it is the collective ‘we’ who are at fault, the westerners dealing directly with terrorism or violent extremism or whatever we’re calling it this week. Western militaries, western governments, western media all default onto ‘Islamic State’ or ‘ISIS’ (the Islamic State in Iraq & Syria or the Shams) or ISIL (the Islamic State in the Levant). They’re relatively accurate translations of the term the group uses for itself in Arabic, ad-Dawlah al-Islāmiyah fī ‘l-ʿIrāq wa-sh-Shām. (It’s currently cool to call them ‘Da’esh’, an acronym of the latter which is also close in sound to an Arabic word meaning ‘destructive’ and which will get you your tongue cut out if you use it in Da’esh controlled areas.)

This isn’t a new discussion. But what is new is that this is first time I have heard a group of Muslims, many of whom live next door to Da’esh, discuss how to refer to the group. It is quite clear that the Muslim participants, all of whom seem very westernised and liberal in their interpretation of Islam (like most of the many Muslims I know), are nonetheless offended that westerners routinely recognise this particular group as being both Islamic and also a state.

It’s a very pertinent point, bearing in mind the fact that, while we drop the occasional bomb and train some people here and there, Tunisia, Turkey, Jordan et al are the ones who will be doing the dirty work in combating these groups. For many of these countries, this is an existential threat: for us, it is not. (We would be doing a lot more if western society was actually facing an existential threat, even if media commentators tell you otherwise during their paid-for rants.)

What should we call it then? There are a wealth of suggestions from the participants: the Un-Islamic State (I thought of that one – no-one else liked it, but I’m writing the blog piece so it gets a mention); the Iraq-Syria Border Terrorists (although better if we could get an insulting acronym out of it); and the Baghdadi Gang (nice because it reduces it to an individual, to a criminal gang).

But Da’esh seems most acceptable to the Muslim participants. Da’esh is what the group is known as routinely in my own neck of the terrorism woods, Somalia as well.

‘But will the western media be able to pronounce it?’ asks a western academic who studies the western media in a western university. The Arabic letter ‘ayn’ is a back-of-the-throat sound and is generally rendered as an apostrophe when transliterated in English (‘da’esh’ pronounced ‘da-quick pause-esh’, ‘qa’ida‘ pronounced ‘ka-quick pause-ih-da’). But that’s quite an ask for the western meeja, so ‘qa’ida’ becomes ‘ka-yee-da’ (close to ‘coyote’, so more pronouncable). Hence ‘ISIS’ or ‘ISIL’ or just plain old ‘Islamic State’. (Let’s ignore, for the moment, the fact that I’m sure those meeja folks can manage to properly pronounce paella and rioja in the tapas bar near the studio once they’re off air.)

The point is that ‘we’, the westerners in the meeja, the military, the government and on the western street, should flex our tongues and our cheeks and our throats in a more constructive manner than we usually do, and stop calling ‘them’ the Islamic State and jihadis and Islamic terrorists. We’re insulting the people who are living with and fighting the threat. Our hundreds killed are their hundreds of thousands. No-one referred to the Irish Republican Army as ‘Catholic Terrorists’ (except maybe in a few Shankhill pubs and UDR drinking clubs) though the majority were Catholics. We didn’t routinely credit the virtual no-go areas of Belfast or Derry or South Armagh as being states. It’s akin to the way we used to racialise crime. So why are we treating the threat from al-Qa’ida and Da’esh differently?

This sits within a bigger problem, the flaw with what the academics call our ‘meta-narrative’ (the big, unifying story our leaders and influencers are telling us). A luminary of my acquaintance, Paul Bell, explained it well in his speech, ‘ISIS and Violent Extremism: Is the West’s Counter-Narrative Making the Problem Worse?’, delivered at the Hedayah Institute in Abu Dhabi (another one of those workshop/conference/courses).

Yes, there is a threat, and Francois Hollande is allowed to call it a ‘war’ when he is interviewed in the immediate aftermath of an attack. He’s French and they’re emotional. But it is not a war for us, it is not a threat to our existence. It is for the people we are inadvertently but consistently offending by Islamicising the problem and giving credit to a gang of terrorists, sadists and criminals who happen to control a bit of territory – for the moment.

So say after me, ‘Da-esh, Da-esh, Da-esh…’

The Attack That Never Was

ON the morning of December 14th reports appeared of a foiled attack on MIA (Mogadishu International Airport), the airport complex in Mogadishu, a city within a city that houses the various manifestations of the UN, the military and political headquarters of the African Union mission in Somalia (‘AMISOM’) various embassies and the obligatory post-conflict zone mixture of security, construction and logistics contractors. Reporting indicated that an attempt had been made to infiltrate the camp from the sea (the runway runs along the shore) but that AMISOM forces had thwarted the amphibious assault, now credited to al-Shabaab.

I rang around the usual suspects. One had heard banging in the early hours but thought it was doors slamming as boys and girls do what boys and girls do in post-conflict zones the world over (some even believing that relationships survive the end of rotation). Another had been told it was Danab, the Somali special forces, doing a night shoot down on the firing range that faces out to sea.

More details emerged: up to five boats, each with ten fighters, had been fought off. Turkish Airlines, which had shown unrivalled daring in being the only international carrier to add Mogadishu to its long list of routes, apparently suspended flights. In the run-up to Christmas and with al-Shabaab’s tradition of mounting attacks on MIA at Christmas (an indirect fire attack on Christmas Day in 2013, a bloody complex attack on Christmas Day 2014), everyone was in a heightened state of alert anyway.

But al-Shabaab didn’t claim the attack. Normally, and without giving them anything akin to credit, respect or honour, al-Shabaab normally claims credit for its attacks, successful or failed, especially the high profile attacks. And, after the obligatory 48 hours that it takes for the alternative view to manifest itself in the media, pretty soon AMISOM was being accused of mounting a deception.

Military deception as a discipline is something I happen to know about, having practiced it a long time ago in Iraq, while based on the Iranian border in Maysaan province. In one of those funny moves the military often makes in the game of chess that is your career, I attended a course on Military Deception ten years after actually doing it for real (I attended the Psychological Operations course at the end of my operational tour in Psychological Operations, so this wasn’t by any means an aberration).

My chum, Colonel Dougie, who was running the course on Military Deception, puzzled me when he gave a health warning before the practical element of the course, noting that some previous students had found themselves becoming quite worked up during the exercise.

About two hours later I was quite worked up in my tweed suit (I was no longer in uniform by this time, although I gave I nod to my past by wearing a regimental tie, which was angrily askew): I was the student Colonel Dougie described. I was infuriated by my uniform-sporting colleagues’ lack of creativity, bemused by their unwillingness to get downright dirty, livid at their risk aversion.

In Iraq we had had a problem: the other side were constantly using indirect fire, mortaring and rocketing, against us. While we had never lost anyone to indirect fire in this particular location, it was wearing down the troops with the constant ‘INCOMING! INCOMING!’ alarms, donning body armour and helmets, crouched in close, darkened bunkers for hours at a time, all done in the knowledge that on one occasion the other side might actually get lucky.

My special little band had the task of doing something about it. (It was us who had briefed the commander on the morale problem he had: so it was only fitting we try to fix it.) We tried a lot of things, and one of them was military deception. A Lithuanian officer in headquarters was apparently an expert in military deception: he was sent up to assist. (The boys couldn’t master his name, so he was known as ‘Boris’.)

We mounted the old washing machine Boris had brought with him on the roof of our block with a satellite dish stuck to the top of it and fenced off the compound. (We filled the barrel of the washing machine with concrete to slow down the cycle and to stop the dish flying off and beheading some random locals fifteen few miles away.) We waited.

There was a pause in the rocketing, a long pause. One of the locally employed civilian cleaners was caught with a video camera: his footage was of the block and the washing machine/satellite dish combo. We had got their attention, certainly.

That wasn’t all we did, of course. The boys patrolled nightly, deliberately being seen near known firing points. We considered faking the destruction of a mocked up rocket team but were dissuaded. We nearly called in an airstrike on what appeared to be a mortar team (but which turned out to be some men stealing some pipes). We bought ourselves a few lulls, and then the mortaring and the rocketing would begin again.

But deception can and does work. The Allies diverted the German High Command’s attention from Sicily to Greece by planting fake documents on a body dumped at sea for the Germans to find, and then invaded Sicily famously recounted in ‘The Man Who Never Was’. D-Day preparations included grand deceptions to deceive the Germans about the likely beachheads. Iraqi forces in 1991 expected an amphibious assault on Kuwait but instead received a land based out-flanking manoeuvre. But the danger of deception in the modern age is credibility. The deception used in 1991 Gulf War both used and compromised the news media, who had dutifully focussed their cameras on Marines and amphibious assault craft. Whether such deceptions would be possible now is debatable, when everything is recordable (see Bellingcat’s tracking of the Buk launcher that allegedly fired the missile that downed flight MH17) but nothing is believable. Truth has become selective truth. Perception has become reality. Perhaps the pre-eminence of credibility, combined with our built-in risk aversion, means deception is no longer viable.

As it happens, I know that stretch of coastline very well, having been in Mogadishu on and off since Christmas 2009. It was always viewed as being relatively safe (as opposed to the city facing side of the camp) because of the jagged coral and the volcanic rock formations that run all the way along that stretch – I used to go and paint watercolours there at the end of the day. Rumour (of which there is never a shortage in either Somalia or in the post-conflict environment generally) had it that a western special forces unit (ibid – they used to run past me while I was painting the same coastline again and again) had attempted a nocturnal landing and, while they had managed it, it was a significant challenge for them, even with all their canoes and night vision goggles and years of crawling out of torpedo tubes and up the legs of oil rigs.

There is a Somali saying, ‘the Somali stands with his back to the sea’, meaning they are a generally landward-looking race. Even now it’s not uncommon to find Somalis who don’t eat fish or who can’t swim and the maritime wealth of the longest coast on mainland Africa is still relatively untapped. But there are a few fishermen and, of course, there were, for a while, more than a few pirates.

But a few fishermen and more than a few pirates does not easily translate into an amphibious assault capability for al-Shabaab. The pirates have been driven away by an international blockade and armed guards on ships. The fishermen sail by the stars and occasionally, on moonless nights, like December 14th, they have to navigate by the coastline. On the occasions when they happen to pick the coastline along MIA to fix their position and head homewards, they get a few warning shots and are sent on their way. Perhaps that is what actually happened.

There is another Somali saying: the truth can never catch up with a widely-spread lie. In the information age, I wouldn’t be so sure.

The image of the stencilled bodies on the Normandy beaches comes from a memorial to mark the 70th anniversary of D-Day. ©rossparry.co.uk syndication/Daily Mail

‘But They’re So Much Better Than Us’

The Myth of Terrorist Communications Superiority

The moment an al-Shabaab cameraman is shot and killed while filming the attack on Janaale, captured on camera: it is unclear which direction the bullet came from

Another day, another al-Shabaab attack video.

Janaale, near Marka town, was occupied by Ugandan People’s Defence Forces serving under the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) flag. The camp was in the process of being dismantled as part of AMISOM force re-posturing, recognising the danger posed to isolated positions in the hinterland by al-Shabaab’s continuing ability to mass hundreds of fighters for set-piece attacks. Unfortunately for the Ugandans that day the re-posturing meant that, while the artillery and armour had been withdrawn, the infantry remained. At dawn on September 1st, al-Shabaab destroyed a nearby bridge (denying reinforcement by land) and then, under a low grey sky (denying air support), attacked.

The President of Uganda and senior military figures are mocked in the video

Released 6 weeks later (this appears to be the standard period), the video unfolds to the usual pattern: a lengthy educational introduction by a luminary, then the attack itself. A suicide attacker initiates the assault (just as it did during the attack on the Burundian position in Leego) and seemingly hundreds of troops fight through the spartan, disorderly seeming AMISOM position. Heavy weapons blaze away, fighters fire from the hip and over their heads. (Did I see two pale fighters, about half way through?) An occasional Ugandan is seen in the distance. At the conclusion of the attack, stockpiles of captured weapons, ammunition, uniforms, identity cards. The dead are made more dead by being shot at close range.

A captured Ugandan is displayed

A novelty: a captured Ugandan chats amiably about being woking up by the explosions, only to find he had been abandoned. Connections, quite possibly artificial, are made: to the killing of civilians in nearby Marka town by AMISOM forces in the aftermath of an IED attack, to the anniversary of Godane’s death in a US airstrike. The product is bookended by footage of the Ugandan president and senior military figures, set-up to look like bluffers, African Comical Ali’s, as they mock al-Shabaab’s weakness and praise their own forces.

Captured AMISOM equipment is displayed

The videos are definitely improving in production quality. The Janaale video is tighter, certainly tighter than the ponderous Mpeketoni video that spent 45 minutes focussing on President Uhuru Kenyatta’s denials of al-Shabaab involvement in the attacks before it actually got down to showing al-Shabaab involved in attacking Mpeketoni (another 45 minutes). The edits are good, split screens, multiple angles. Six different cameramen were involved, laboriously proven by six different views of the suicide attack that initiated the attack. And the gamer’s eye view of an attack can’t be beaten. It almost feels like you’re there.

Oddly, though, no mention of the ongoing purge within al-Shabaab of those who seek a shift of allegiance to the Islamic State.

‘Slick,’ says a colleague, also former military, also in his 40s. ‘Sophisticated,’ says a female acquaintance working for a friendly government, also in her 40s. ‘But they’re so much better than us,’ despairs another (also in his 40s).

But a 14 year old wouldn’t say that: they would find these products laughable. Why is it so long? (Tut.) And why don’t you actually see anything? (Sigh.) Are these videos actually authentic? (Tut.) Haven’t they heard of Go-Pro? (Tut.) And how are you meant to download something 30 minutes long onto your phone? (Tut.) Aren’t there highlights of the best bits? (Sigh.) Booorrriiing. (Tut. Sigh.)

Situations Vacant: al-Shabaab Cameraman

The Janaale video is ripe with specifics for the 14 year old to rip apart. During one of the many scenes of ‘men standing in a field firing at distant bushes,’ there is a puff of earth in front of the cameraman… A pause… The image slides to the left and hits the ground… ‘The martyrdom of the cameraman, brother Abdulkarim al-Ansari,’ announces the slate.

How amusing would a 14 year old find that? Your cameraman gets shot and you actually include it in the video…? Epic fail. Lucky they had six of them! Who’d be an al-Shabaab cameraman?

What we are facing in the information war is not the over-whelming creative sophistication and technological aptitude of the other side: the problem there lies more with the lack of creativity and the technical ineptitude of many of those we choose to implement our response. Sometimes it is much simpler: volume and a bit of initiative, for example. While institutions focus on what might go wrong, the enemy is focussing on what might go right.

As Dr Neville Bolt of the Department of War Studies at King’s College, London, points out, we are moving towards a new phase in the way institutions communicate: we have moved from 80s-style complete control of communications (think Falklands – print this); through the millennium period of ‘control-management’ (think spin-doctors and embeds); and, now, institutions engage in management-responsiveness (‘I will be answering your Tweets questions at midday today…’).

But the process of development is not finished: next, predicts Dr Bolt, comes Pro-active Responsiveness, the ultimate delegation of messaging (with all the risk that brings). He attaches an arbitrary ‘2024’ deadline for that to come about. There is now so much communicating going on that governments, militaries and other lumbering monstrosities cannot hope to control it but must instead engage with it through trusted and maybe not-so-trusted advocates, and in the knowledge that there will be ‘epic fails’.

In some ways, that is how terrorists and insurgents are already communicating, as if it is Dr Bolt’s 2024: totally off the lead, making mistakes (like getting shot dead while filming), but getting a message out nonetheless.

But it is also how gaming communities and trendy clothing brands and media houses and bars and restaurants are already communicating – groups that are on our side but not yet On Our Side. (They probably are not yet On Our Side because we haven’t asked them if they want to be on our side, because they have beards or piercings or didn’t go to the same schools as us.)

Come to think of it, it only seems to be 40-somethings like me and my chums, and institutions, with their collective, 40-something mindsets, that aren’t communicating this way. Like all wars this war this will be a young man’s game, but this time we should perhaps consider giving the young men and, increasingly, the young women, a say in the strategy rather than just asking them to do the dirty business of getting killed (albeit now on camera).