The Myth of Terrorist Communications Superiority

The moment an al-Shabaab cameraman is shot and killed while filming the attack on Janaale, captured on camera: it is unclear which direction the bullet came from

Another day, another al-Shabaab attack video.

Janaale, near Marka town, was occupied by Ugandan People’s Defence Forces serving under the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) flag. The camp was in the process of being dismantled as part of AMISOM force re-posturing, recognising the danger posed to isolated positions in the hinterland by al-Shabaab’s continuing ability to mass hundreds of fighters for set-piece attacks. Unfortunately for the Ugandans that day the re-posturing meant that, while the artillery and armour had been withdrawn, the infantry remained. At dawn on September 1st, al-Shabaab destroyed a nearby bridge (denying reinforcement by land) and then, under a low grey sky (denying air support), attacked.

The President of Uganda and senior military figures are mocked in the video

Released 6 weeks later (this appears to be the standard period), the video unfolds to the usual pattern: a lengthy educational introduction by a luminary, then the attack itself. A suicide attacker initiates the assault (just as it did during the attack on the Burundian position in Leego) and seemingly hundreds of troops fight through the spartan, disorderly seeming AMISOM position. Heavy weapons blaze away, fighters fire from the hip and over their heads. (Did I see two pale fighters, about half way through?) An occasional Ugandan is seen in the distance. At the conclusion of the attack, stockpiles of captured weapons, ammunition, uniforms, identity cards. The dead are made more dead by being shot at close range.

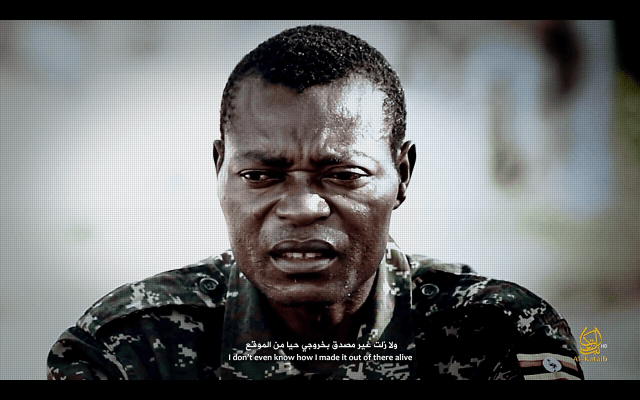

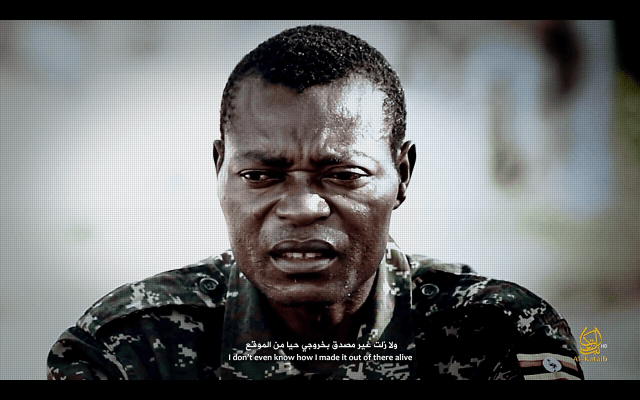

A captured Ugandan is displayed

A novelty: a captured Ugandan chats amiably about being woking up by the explosions, only to find he had been abandoned. Connections, quite possibly artificial, are made: to the killing of civilians in nearby Marka town by AMISOM forces in the aftermath of an IED attack, to the anniversary of Godane’s death in a US airstrike. The product is bookended by footage of the Ugandan president and senior military figures, set-up to look like bluffers, African Comical Ali’s, as they mock al-Shabaab’s weakness and praise their own forces.

Captured AMISOM equipment is displayed

The videos are definitely improving in production quality. The Janaale video is tighter, certainly tighter than the ponderous Mpeketoni video that spent 45 minutes focussing on President Uhuru Kenyatta’s denials of al-Shabaab involvement in the attacks before it actually got down to showing al-Shabaab involved in attacking Mpeketoni (another 45 minutes). The edits are good, split screens, multiple angles. Six different cameramen were involved, laboriously proven by six different views of the suicide attack that initiated the attack. And the gamer’s eye view of an attack can’t be beaten. It almost feels like you’re there.

Oddly, though, no mention of the ongoing purge within al-Shabaab of those who seek a shift of allegiance to the Islamic State.

‘Slick,’ says a colleague, also former military, also in his 40s. ‘Sophisticated,’ says a female acquaintance working for a friendly government, also in her 40s. ‘But they’re so much better than us,’ despairs another (also in his 40s).

But a 14 year old wouldn’t say that: they would find these products laughable. Why is it so long? (Tut.) And why don’t you actually see anything? (Sigh.) Are these videos actually authentic? (Tut.) Haven’t they heard of Go-Pro? (Tut.) And how are you meant to download something 30 minutes long onto your phone? (Tut.) Aren’t there highlights of the best bits? (Sigh.) Booorrriiing. (Tut. Sigh.)

Situations Vacant: al-Shabaab Cameraman

The Janaale video is ripe with specifics for the 14 year old to rip apart. During one of the many scenes of ‘men standing in a field firing at distant bushes,’ there is a puff of earth in front of the cameraman… A pause… The image slides to the left and hits the ground… ‘The martyrdom of the cameraman, brother Abdulkarim al-Ansari,’ announces the slate.

How amusing would a 14 year old find that? Your cameraman gets shot and you actually include it in the video…? Epic fail. Lucky they had six of them! Who’d be an al-Shabaab cameraman?

What we are facing in the information war is not the over-whelming creative sophistication and technological aptitude of the other side: the problem there lies more with the lack of creativity and the technical ineptitude of many of those we choose to implement our response. Sometimes it is much simpler: volume and a bit of initiative, for example. While institutions focus on what might go wrong, the enemy is focussing on what might go right.

As Dr Neville Bolt of the Department of War Studies at King’s College, London, points out, we are moving towards a new phase in the way institutions communicate: we have moved from 80s-style complete control of communications (think Falklands – print this); through the millennium period of ‘control-management’ (think spin-doctors and embeds); and, now, institutions engage in management-responsiveness (‘I will be answering your Tweets questions at midday today…’).

But the process of development is not finished: next, predicts Dr Bolt, comes Pro-active Responsiveness, the ultimate delegation of messaging (with all the risk that brings). He attaches an arbitrary ‘2024’ deadline for that to come about. There is now so much communicating going on that governments, militaries and other lumbering monstrosities cannot hope to control it but must instead engage with it through trusted and maybe not-so-trusted advocates, and in the knowledge that there will be ‘epic fails’.

In some ways, that is how terrorists and insurgents are already communicating, as if it is Dr Bolt’s 2024: totally off the lead, making mistakes (like getting shot dead while filming), but getting a message out nonetheless.

But it is also how gaming communities and trendy clothing brands and media houses and bars and restaurants are already communicating – groups that are on our side but not yet On Our Side. (They probably are not yet On Our Side because we haven’t asked them if they want to be on our side, because they have beards or piercings or didn’t go to the same schools as us.)

Come to think of it, it only seems to be 40-somethings like me and my chums, and institutions, with their collective, 40-something mindsets, that aren’t communicating this way. Like all wars this war this will be a young man’s game, but this time we should perhaps consider giving the young men and, increasingly, the young women, a say in the strategy rather than just asking them to do the dirty business of getting killed (albeit now on camera).

Interesting that the la-la who wakes up in the US and decides he/she wants to be a jihadi tools up with assault rifles, pistols, body armour and pipe bombs – while their UK brethren (because they are all symbiotically linked, ye ken?) has to make do with a steaky bought from Morrison’s. There’s a lesson in there somewhere, isn’t there?

Interesting that the la-la who wakes up in the US and decides he/she wants to be a jihadi tools up with assault rifles, pistols, body armour and pipe bombs – while their UK brethren (because they are all symbiotically linked, ye ken?) has to make do with a steaky bought from Morrison’s. There’s a lesson in there somewhere, isn’t there?